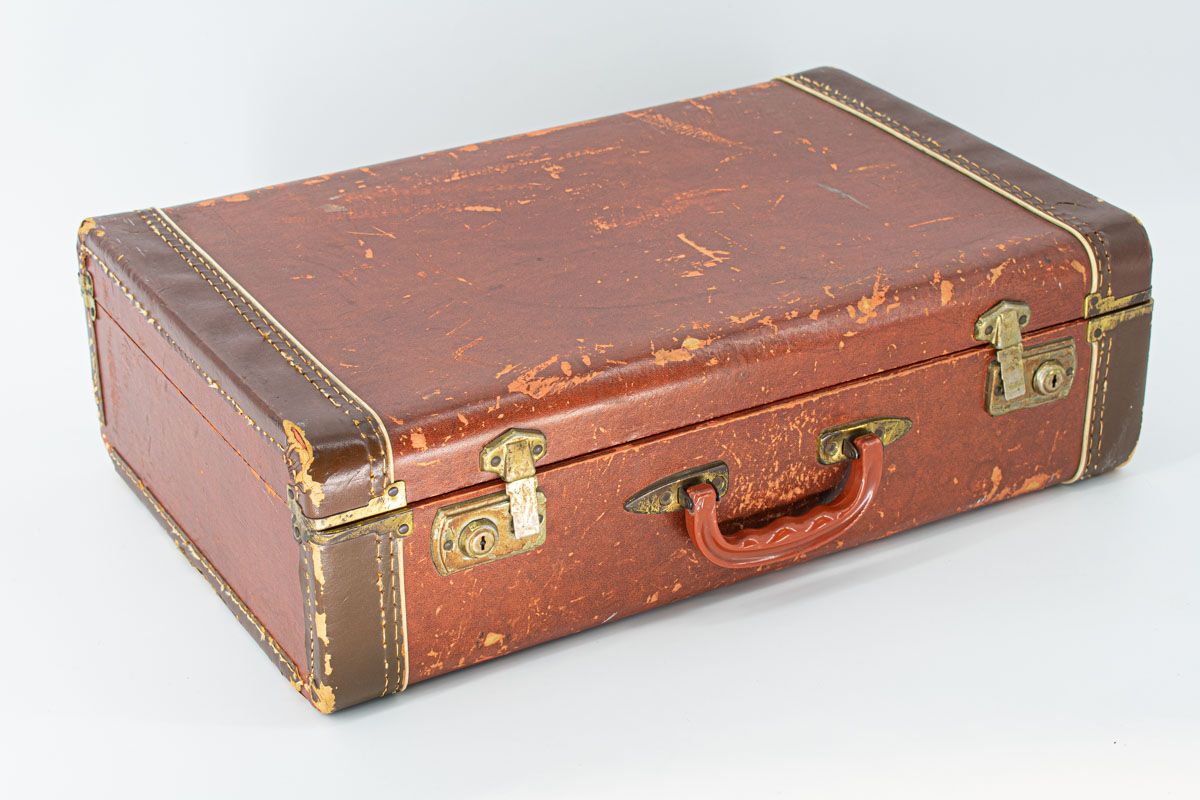

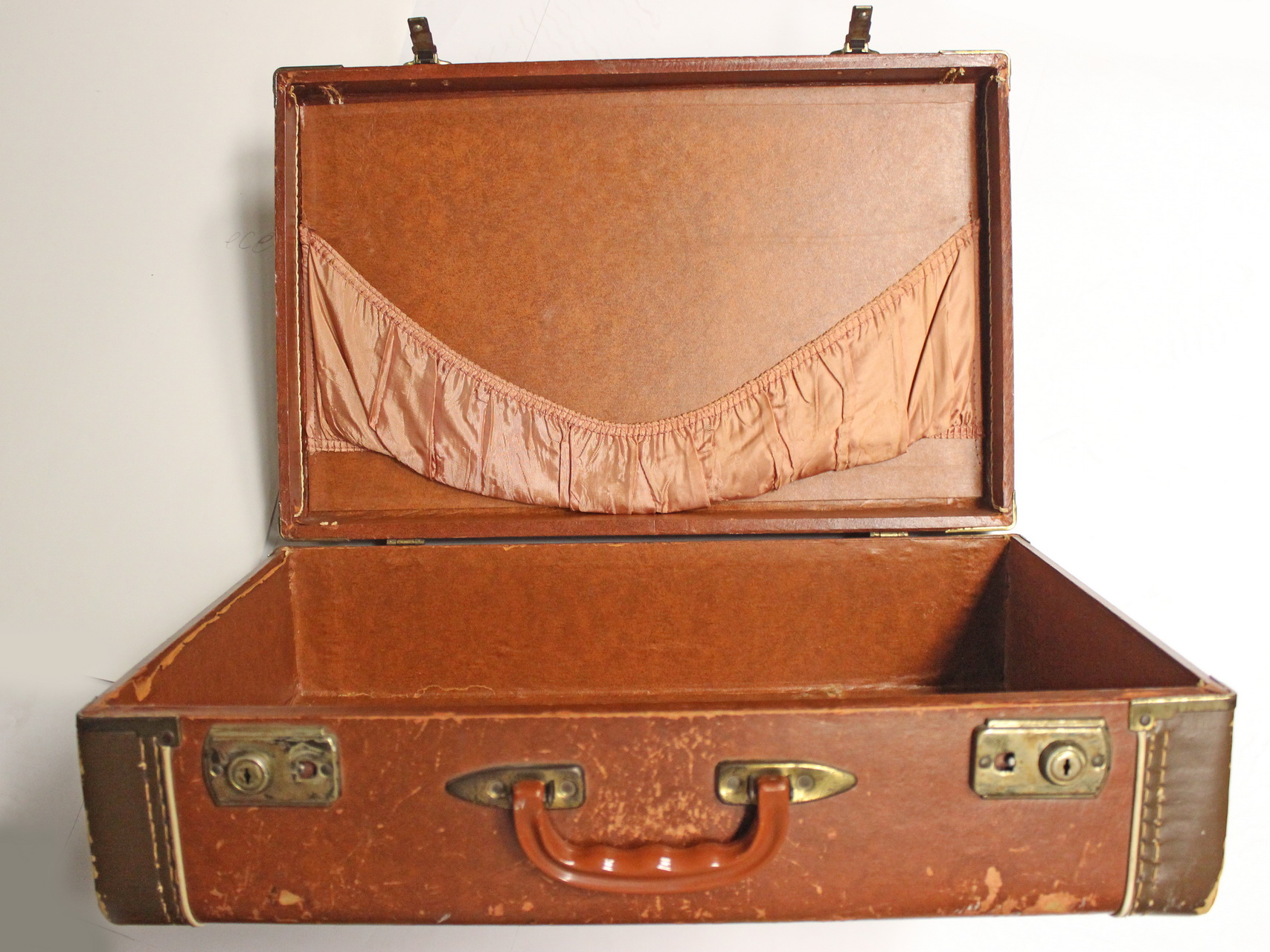

It is hard to imagine that a simple, unremarkable suitcase among dozens of similar items could serve as a symbolic, even somewhat epochal exhibit in the history of an institution whose archival collection holds over 400,000 artifacts. However, this very object visualizes, at first glance, seemingly unrelated yet, in fact, extraordinarily important themes in the discourse of 20th-century Ukrainian military history.

This briefcase belonged to an eleven-year-old boy who, together with his family, was forced to leave Ukraine in 1944 due to the advancing front near Lviv.

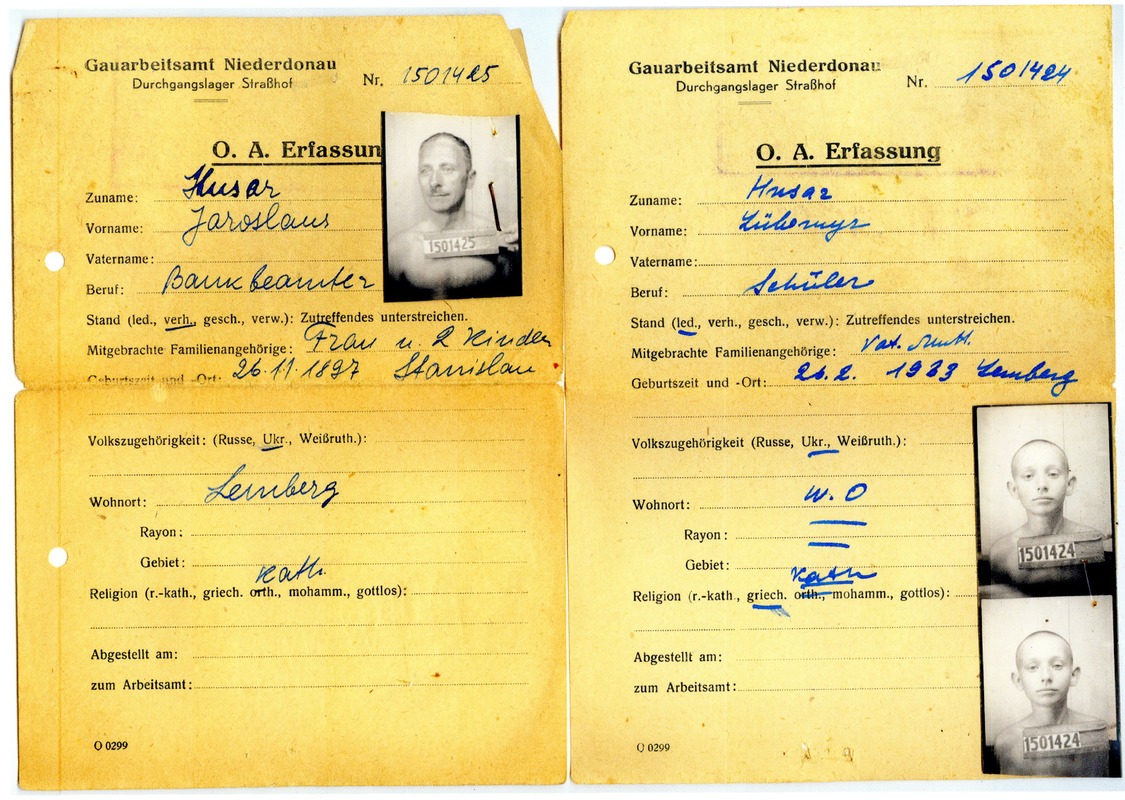

His great-grandfather was a priest of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. His grandfather was a lawyer who, in contrast to the Moscow-centric nationalists, organized a branch of the "Prosvita" society in a town founded near the former capital of the Galician-Volhynian state. His father was a soldier in the U.S.S. Legion, a chotar (officer) in the Ukrainian Galician Army, a veteran of the Chortkiv Offensive. Although he did not remain active in public life, he nevertheless came under the watch of the NKVD when the Soviets arrived, and his family was included in the list for deportation. Distant relatives, among other members of the OUN (Ukrainian Nationalist Organization) marching group, were executed by the Nazis in Babyn Yar in 1942.

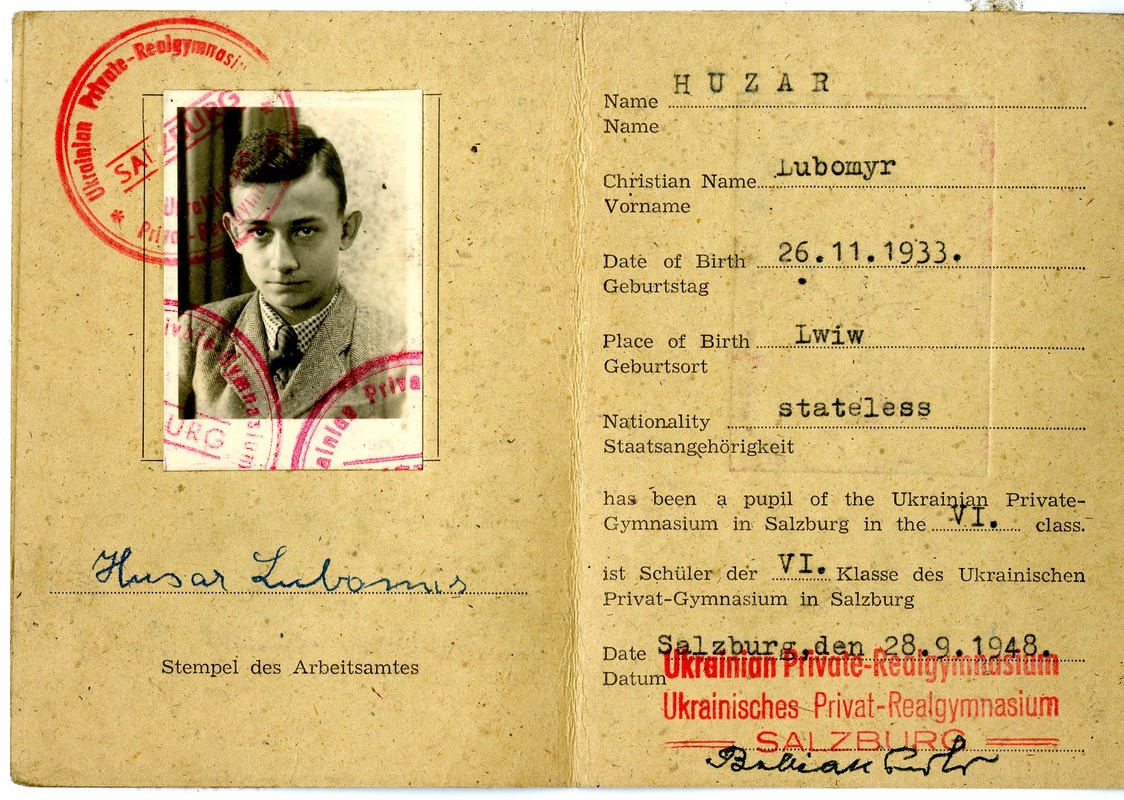

The young boy’s documents, like a travel journal, contain numerous annotations, including "D.P." (Displaced Person, in Austria), indicating he was in transit camps, and even "stateless."

In fact, this is the fate of millions of our compatriots who, amid the upheaval of the two world wars, and even today under foreign aggression, were forced to flee everything due to the fear of persecution for their roots—obtaining Nansen passports or becoming citizens of another country.

This same boy was destined to gain a brilliant education, join the ranks of leading figures of Ukrainian political emigration, serve the national community in the U.S. and papal Rome, and, ultimately, return to his homeland after the restoration of independence, leading the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

The words of Blessed Lubomyr Husar, "Ukraine is not divided into west and east. It is divided into those who love Ukraine and those who do not," have never been more relevant in these fateful times for our country. Therefore, it is no surprise that this "unremarkable" suitcase, once belonging to a man—a moral authority for many generations both in Ukraine and beyond—is one of the markers of the Ukraine-oriented museum space.