The topic of captivity, long neglected during the Soviet era, was first raised by museum professionals in the newly created Ukraine-centered exhibition in the mid-1990s. A compelling witness to the tragedy of millions of prisoners became the death registration books of "Groslazaret" – a structural division of stationary Nazi camps No. 301 and No. 357 for sick and wounded Soviet prisoners of war. It was established in December 1941 after the occupation of the town of Slavuta in the Kamianets-Podilskyi region (now Khmelnytskyi).

Inhumane conditions of captivity, hunger, cold, epidemics, and physical abuse almost entirely deprived the prisoners of "Groslazaret" of any chance of survival. According to research, from 1941 to 1944, more than 150,000 prisoners of war were shot or murdered here, the majority of whom are considered missing.

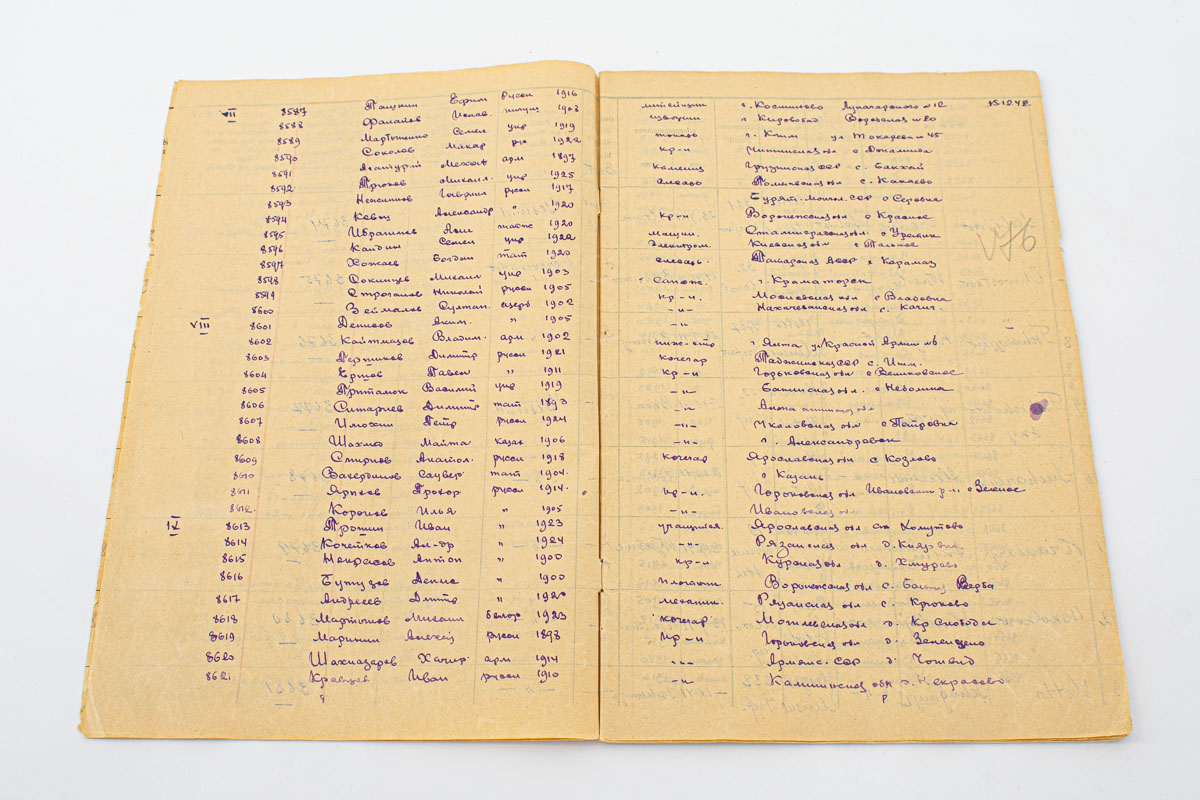

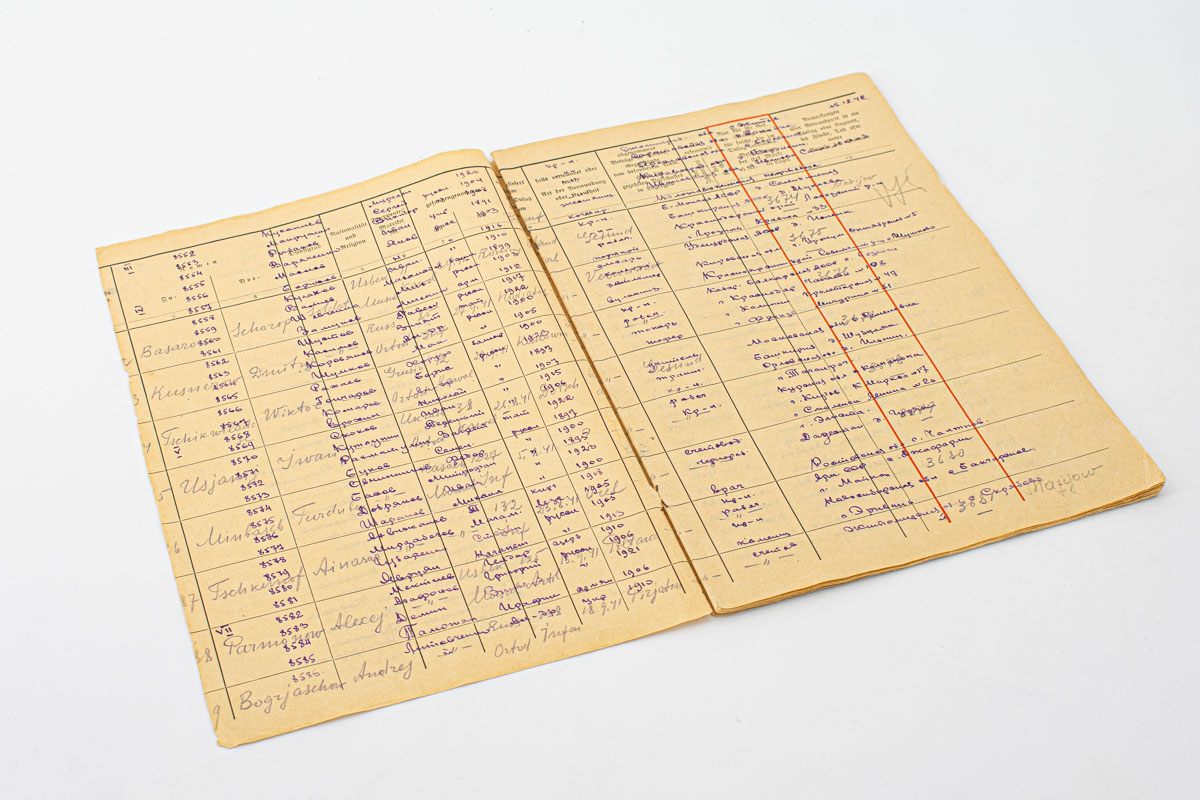

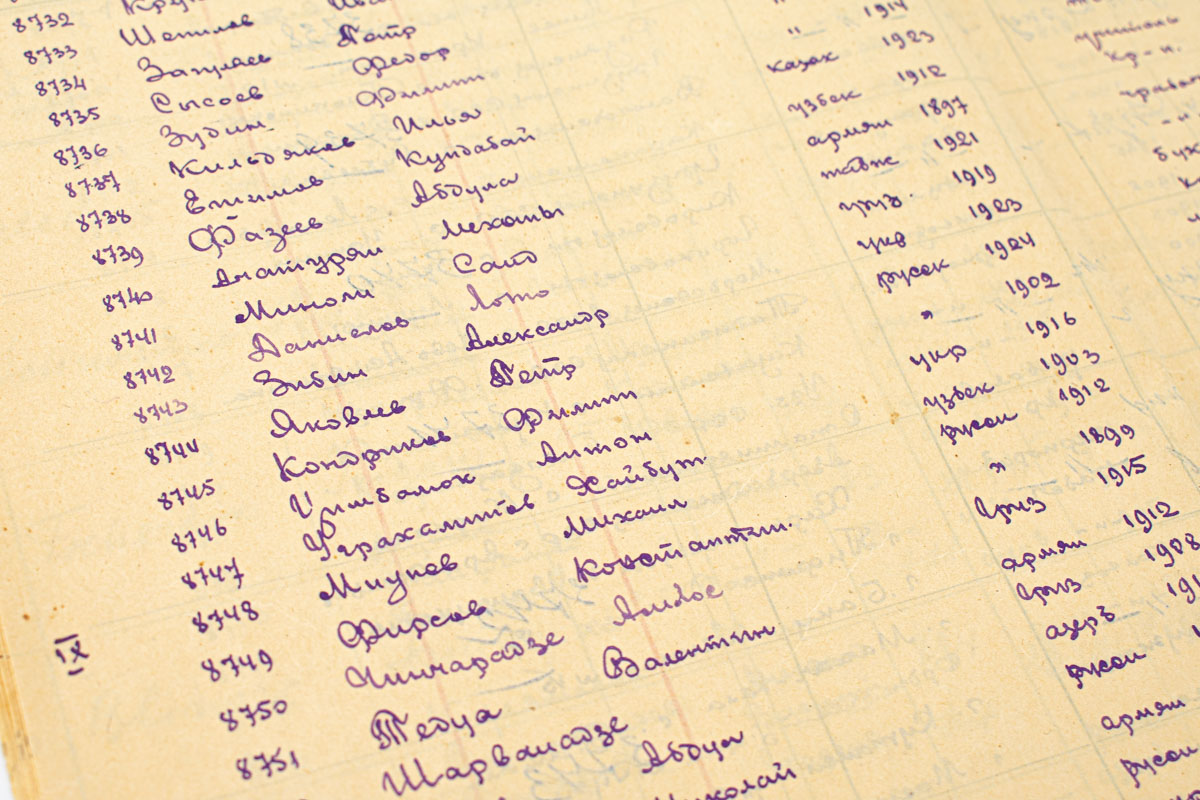

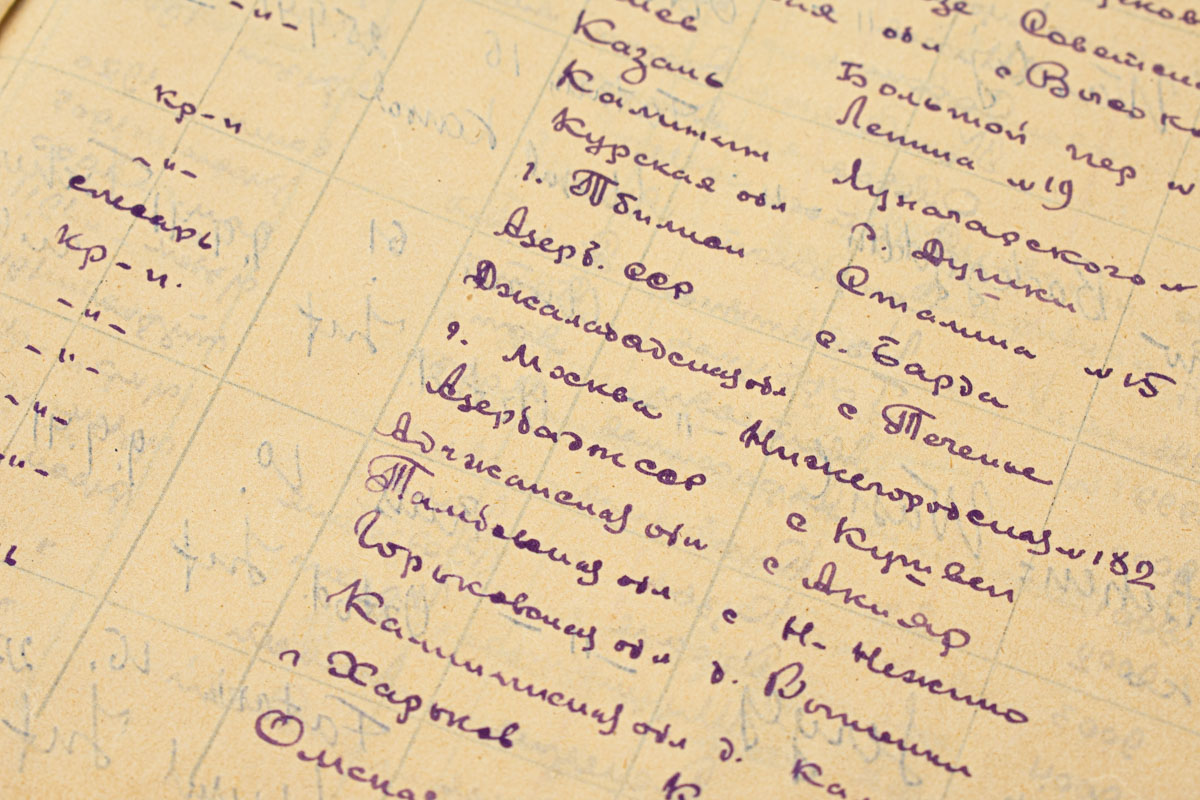

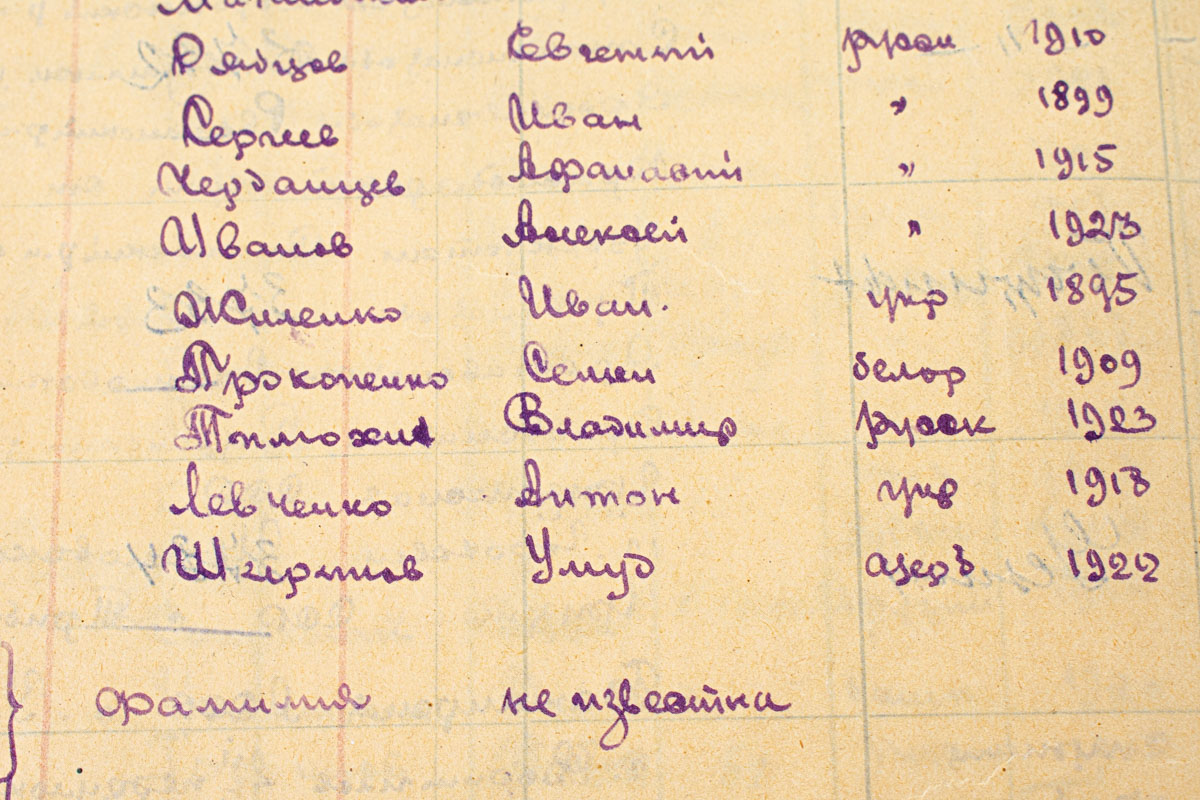

The death registration books, which contain more than 18,500 names of Red Army prisoners from 57 nationalities, represent a sort of martyrology that was secretly maintained at great personal risk by the prisoners themselves: a doctor from Adygea, Adzhi-Aitench Shakhan Chomokov, and a Ukrainian, Hryhorii Ostapenko, a former history teacher at Kirovohrad Pedagogical Institute.

The camp regime was designed solely to destroy as many as possible and break the prisoners morally, leaving no room for any resistance. However, in early 1943, prisoner Roman Lopukhin formed an underground group, which included Shakhan Chomokov and Hryhorii Ostapenko. Over six months, the 82 partisans dug a 95-meter tunnel beyond the camp’s boundaries. On November 23, 1943, only 15 prisoners managed to escape through this tunnel. Among them was Hryhorii Ostapenko, who carried three books documenting the deaths. Later, all the escapees joined the Kamianets-Podilskyi partisan group.

These rare items were transferred to the museum’s collection from the Republican exhibition "Partisans in the Fight Against the German-Fascist Invaders" in the 1980s. For nearly 20 years, researchers at the Memorial studied the history of the writing of this martyrology. After working with the existing lists (it should be noted that these were created in Nazi prisoner registration books, filled in with a simple pencil in German, and then prisoners added the names of the deceased in small handwriting using ink pens in Russian), and consulting archival materials, the museum staff reached out to witnesses and survivors of the tragedy, starting correspondence with former prisoners.

The restoration of names from oblivion and informing families about the burial place of their loved ones is, first of all, the essence of the research work, and second, the resulting documentation and testimonies from relatives during correspondence have become an integral part of the museum’s collection.

In the context of the ongoing large-scale Russian-Ukrainian war, there are currently camps/colonies for prisoners of war in the territories occupied by the enemy, where unbearable conditions, torture, and abuse prevail, and where the enemy conducts mass executions of prisoners to hide their torture and actions that violate international humanitarian law and the Geneva Conventions on the protection of war victims. Ukrainians understand better than anyone else that #CAPTIVITY KILLS.