The "OST" patch, intended for residents from the "eastern territories" who were forcibly taken to Germany for labor during the Second World War, was donated to the Memorial from the collections of the State Historical Museum of the Ukrainian SSR. The sign had originally come from the exhibition "Ukrainian Partisans in the Struggle Against the German-Fascist Invaders," which was held in Kyiv from 1946 to 1950. Unfortunately, there is no information about the owner of this item. However, under the Soviet paradigm, this was not considered significant, as such materials were seen merely as evidence of German crimes, rather than in the context of the fate of each individual.

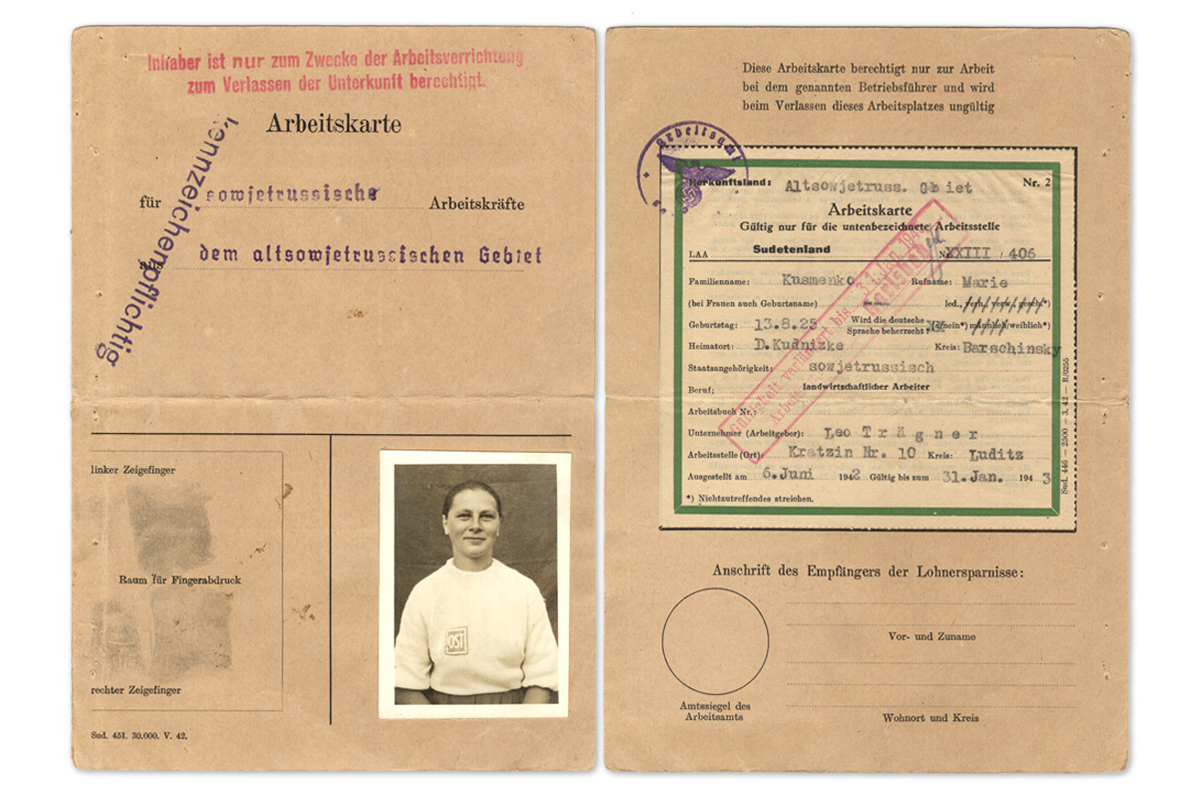

In total, about 2.4 million workers were taken from Ukraine during the Nazi occupation, which accounted for 48% of all those deported from the Soviet Union. Ostarbeiters ("eastern workers") was the term the Nazis used for a multi-ethnic group of civilian workers from territories that had been part of the USSR before 1939, clearly marking their distinct social and legal status within the Third Reich. The main regulations regarding the use of "labor force" were outlined in the Ostarbeiter regulations (Ostarbeitererlasse) of February 20, 1942, which were prepared by a special commission of the Reich Main Security Office of Germany. Every worker was issued a labor book or a work card. It was mandatory to wear the "OST" badge on outer clothing. Maria Yefimenko, from Kyiv region, wrote to her relatives: "And where is our people not suffering now, where aren’t we… everywhere you look – and it’s all ’OST.’ They marked us here like sheep…". Letters were almost the only means of communication between the deported and their relatives who remained in Ukraine.

The living conditions of these workers varied. Those involved in industrial production faced the harshest conditions—exhausting labor, barracks, hunger, and frequent illness. Those taken for agricultural work or to serve as domestic workers in households were completely dependent on the attitude of the employers.

Only decades later, those of our compatriots who met decent people abroad were able to share stories about the kindness of "bauers" and the help and sympathy of German workers. After the war, the majority of Ostarbeiters underwent Soviet scrutiny in front-line and army camps, transit points of the Ministry of Defense, and NKVD filtration points. Many were accused by special services of "collaboration with the occupiers." Whether they went to Germany voluntarily or by force, for the Soviet authorities, it did not matter. Despite the fact that in 1946, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg recognized the use of forced foreign labor in Nazi Germany as a crime against humanity and a violation of international law, the Soviet Union subjected them to humiliation, discrimination, and often persecution, with the stigma of "worked for the enemy, was in Germany."

Only during the years of independence did Ostarbeiters, among other communities despised by the Kremlin dictatorship, gain their own history and memory. Museum workers contributed to this effort through extensive research, the creation of thematic exhibits, and the publication of comprehensive scientific and documentary works such as "It Was Captivity..." and "Ukrainian Ostarbeiters."